It’s been two weeks, but better late than never. After I read Jessica’s zong zi post on Food Mayhem, images of amber tedrahedra just wouldn’t leave me alone. I talked to my mom about them, and I could hear her voice crackle with sweet memories over the phone. We haven’t had these sweet little things for years. We used to eat them by the dozens every lunar May. Like most Saigonese, we didn’t do anything huge to celebrate Tet Doan Ngo, but bánh ú tro was too scrumptious a tradition to pass.

Each pyramid is just a little over an inch tall, whichever way you roll it. It’s unclear whether the traditional zongzi grew smaller when Chinese immigrants share the recipe with their Vietnamese neighbors, or only the dessert zongzi (jianshui zong) is favored by the locals over savory types. Most Vietnamese have also long dissociated this sticky rice snack with the Chinese reason behind Duanwu festival, if not to assign the Fifth of Lunar May to commemorate the death anniversary of Vietnam’s legendary Mother Âu Cơ, kill off bad bugs, make ceremonial offerings to family ancestors, or simply bathe in the summer solstice’s endless sunlight. Whatever meaning someone chooses to celebrate (or not celebrate) Duanwu (Đoan Ngọ in the Vietnamese language), he can enjoy bánh ú tro all the same. And if he lives in Hội An, there’s a big chance he actually participates in making them too.

The people of Hoi An don’t make a living with bánh ú tro year round, but they keep the tradition with earnest. Within four days, 1st-4th of lunar May, everybody makes bánh ú tro. The fifth day, everybody eats bánh ú tro. The sixth day, things get back to normal. In Saigon’s markets, bánh ú tro start showing up a week or two before the Fifth, and disappear right after, my mom recalled. So when I told her that I was going to search for them after I read Jessica’s post, she said “fat chance”.

Why such rarity? After all, bánh bía, also adapted from the Chinese and also originally made just for one specific festival, shines its face all year long in every bakery and sandwich shop these days. Well, the recipe for bánh ú tro turns out to be real hard, and it’s not just the wrapping stage. The best bánh ú tro, according to Hoi An banh makers, must be wrapped with “kè” leaves from the mountains of Huế. The cleanly washed sticky rice is soaked in sesame ash water overnight (sesame plant burnt into ashes, mixed with water and sifted through sand). The ash water turns sticky rice grains into semi-powder form, giving bánh ú tro a clear amber look and a strangely light texture, unlike any other sticky rice concoctions. No wonder “ash” (tro) is part of the banh’s definitive name. (If you look at jianshui zong recipes, you’ll find lye water or alkaline water listed. More correct terms perhaps, but the horrid image on Wikipedia’s page on lye takes away my appetite. “Ash” even has a romantic ring to it, and this banh is made for a poet after all.) A bit of alum is put in the ash water to somehow keep each banh from falling apart.

Now of course sesame plants aren’t growing in everyone’s backyard to burn, so just any coal ash would do, as long as you sift the ash water carefully to avoid big pieces of charcoal in your sticky rice. Some different source suggests ash from mangrove firewood, dissolved in water for a month, but it seems to be just another grandmother’s special recipe varying by the regions. After soaking the rice for 1-3 nights, take it out and wash with cold water again.

The wrapping leaves, too, vary from place to place. Kè leaf is obviously not the most popular, as bamboo leaf and reed leaf, in their slender shape and earthy fragrance, do the job just as well. Banana leaves can be cut into wide strips to imitate bamboo leaves. Skilled banh makers can also control the colors: older leaves give darker hues, substituting ash with white lime paste(*) lets bánh ú tro have the natural green shades from the leaves, while red lime paste causes a reddish amber shine.

Nonetheless, there exists a common wisdom regardless of ingredients: burn an incense stick when you drop the banh into water for boiling, when the incense burns out, the banh is done. Usually that takes four hours.

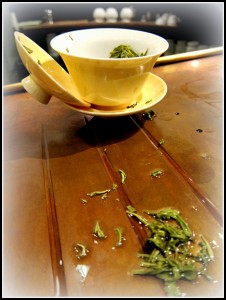

Let cool, bánh ú tro is more firm than chewy. There you can still see silhouettes of individual grains on the outside, but each banh is a solid tedrahedron of defined edges and uniform texture. It unwraps easily, parallel thread marks of bamboo leaf veins imprint on the smooth and fulfilling surfaces. It’s hardly sticky, unlike bánh ít and bánh dầy (also made from sticky rice). And it’s light. The banh’s are tied together in bundles of ten, and I can eat all ten in one sitting. (I can hardly finish one bánh ít in one sitting.) Funny, “ít” means “small in quantity”, and “ú” means “chubby”.

The traditional bánh ú tro of the North and Central Vietnam is just that, a plain chunk, good by itself to some and must be accompanied by honey or sugar to others. Then with time it got a sweetened red bean paste filling. Then a sweetened mung bean paste filling. Then a sweetened grated coconut filling. I grew up eating the red bean kind every year and thought it was the only kind. So I jumped at the first bunch I saw at Kim’s Sandwiches last Sunday, twelve days after the Fifth of Lunar May. The bunch was tied together by green nylon strings. I hurried home, unwrapped, took a bite. My mom called.

– Mom, I found them!

– Really?!?! How are they?

– Good, but why’s there no bean paste?!

Should’ve gotten the red string bunch instead.

———————————————————————-

Bánh ú tro ($3.75/10 pieces) from Kim’s Sandwiches

(in the Lion Supermarket area)

1816 Tully Rd 182, San Jose, CA 95111

(408) 270-8903

(*) Lime paste is used to eat with betel leaves and areca nuts.

Click here for a recipe of bánh ú tro (Vietnamese zong zi)

———————————————————————–

Previously on Sandwich Shop Goodies: bánh bía (Vietnamese adapted Suzhou mooncake)

Next on Sandwich Shop Goodies: corn xôi

We’ll have to get the ones with mung bean paste next year. Then you can edit this post. I like stuff with mung beans.

Problem is I don’t have a lunar calendar to see when the day is. The bean ones may be sold out if we get there too late.

That looks good, I especially like how the leaves are used to make a pretty little package for it to come in.

The best sandwich place I have ever been to is Melt Sandwiches in White Plains, NY. All the meat is smoked on premises and the chef makes amazing sauce/topping combinations. Hands down my favorite sandwiches!